Spinal Injury Accident Scene Management

Spinal cord injury most commonly result from road trauma such as vehicle collision, overturn, unrestrained or ejected occupants and motorcycle accidents. These combined with falls from a height, cyclists, shallow diving, collapsed football scrums and other contact sport injuries warrant immediate concern of damage to the spine and spinal cord, being attributed to around 80% of all spinal cord injuries. At the accident scene always assume a spinal injury has occurred until proven otherwise by x-rays and a medical specialist. Call emergency services. Do not move the person unless in immediate danger.

Extreme care must be given when moving unconscious patients and equally to those conscious reporting back or neck pain, and those who describe altered sensation or poor limb motor function. Encourage the person to not move. Post accident, occasionally paraplegics and tetraplegics (quadriplegics) recall walking, and may still be able to walk a short distance before paralysis fully sets in. This and any unnecessary movement is to be avoided, as it can cause further damage to the spinal cord.

SPINAL CORD INJURY MOTORCYCLE ACCIDENT SCENE

If the casualty is wearing a full-face motorcycle helmet and airway access is critical use a two person technique to remove it. One braces the neck in the neutral position by placing the palms of their hand either side of the neck wrapping fingers around firmly enough to support and stabilize without cutting off oxygen or blood supply. The second person unbuckles the helmet jaw strap, spreads the lateral margins of the helmet apart as much as possible to gently ease the helmet off. Tilting the helmet forward slightly can avoid flexion of the neck when sliding the back of the helmet up. Also take care not to trap the nose.

SPINAL CORD INJURY DIVING ACCIDENT SCENE

Often those who sustain a spinal cord injury when diving are found floating face down. Immediate action to reposition into a neutral supine (face up) position is obviously vital though care must be taken to maintain head, shoulder and hip alignment when doing so by performing a log roll. Rotation or twisting of the spine can cause further injury to the spinal cord. In deep or rough waters transfer the person to the shoreline as smoothly as possible, again take great care to maintain head shoulder and hip alignment. Any undue movement of the spine could mean the difference between walking again or never.

RE-POSITIONING PERSONS WITH SUSPECTED SPINAL INJURY

Keeping the head and neck carefully placed in a neutral (head shoulders and hips aligned) position splinting is best achieved with a rigid collar (neck brace) of appropriate size. Tapes placed across the forehead and collar help reduce further damage to the spinal cord from movement, unrelieved misalignment, and compression. If attempting neutral alignment exacerbates pain or the cervical vertebrae are locked in a position of torticollis (severe bend) abandon repositioning, the neck can be splinted in the position found. Thoracic and lumbar spinal injuries must also be assumed and treated by carefully aligning the trunk and hips.

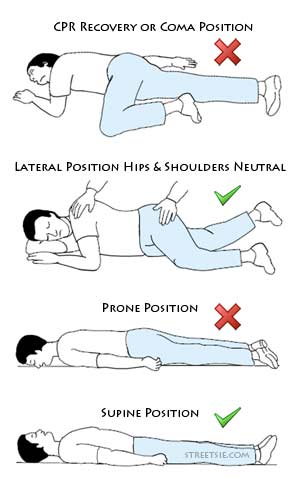

Ask the casualty to keep their arms crossed on their chest during turning or lifting, the entire spine must be kept in the neutral position. In a neutral supine (on back facing up) position there is risk of passive gastric regurgitation and aspiration (inhalation) of fluids. This can be avoided by tracheal intubation (a tube from mouth to lungs), the ideal method of securing an airway in unconscious casualties. Be aware the prone (on stomach facing down) position can compromise respiration particularly in tetraplegics (quadriplegics).

RESUCITATION AND AIRWAY ACCESS

Resuscitation and clear airway access override the importance of spinal alignment especially in unconscious patients. When intubation cannot be performed the patient may need to be log rolled into a 70-80 degree lateral (on their side) position during resuscitation. With the head constantly supported in the neutral position secretions can drain from the mouth. Even with a rigid collar applied this position is unstable and should be avoided unless completely necessary. Also avoid using the head-tilt method during mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. When possible, administer high concentration oxygen.

The necessity of clear airway and oxygen for spinal injury patients is similar to those of other trauma. Any condition causing inadequate arterial oxygen saturation (less than 90%) warrants concentrated oxygen. If the person cannot breathe and get enough oxygen they have much more than a spinal injury to worry about. A laryngeal mask airway (LMA) may be used but it will not prevent inhalation of vomit and other fluids. Avoid suctioning tetraplegics as it may stimulate the vagal reflex, aggravate bradycardia (slow heart rate), and occasionally bring on cardiac arrest. When suction is necessary vagal effects can be minimized by administering atropine and oxygen beforehand.

INTRAVENOUS AND MEDICAL ACCESS

With airway access secured establish intravenous (IV) access. The person may have multiple injuries and require injections or IV fluids. Usually delivered by Paramedic, Ambulance, or Physician aware in cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord injury a patient’s hyposensitivity due to sympathetic paralysis can occur and therefore are easily over-infused. Cutting off restrictive clothing, rolling up shirt sleeves and clearing space around the patient allows fast delivery of IV medications when medics arrive.

PERFORM BASIC MEDICAL CHECKS

Check respiratory (breathing) rate and depth. Often tetraplegia and high thoracic paraplegia involves paralysis of the intercostal muscles (between ribs) causing shallow breathing, as the person relies on their diaphragm alone to breathe. Check pulse, blood pressure, level of consciousness, and pupil responses to light. Abnormalities in these can indicate neurological (nerve) distress, common among people who have just suffered a spinal cord injury.

Examine head, chest, abdomen, pelvis and limbs for obvious signs of bruising and trauma. Perform a pinch test on the person?s feet and hands, where no response is given, move up the limbs and body until a response is given. Generally, the greater loss of sensation, the higher position of spinal cord injury. Loss of muscle tone, strength, movement, and reflex action may also present in paralyzed limbs. If the back is exposed spinal deformity or an increased interspinous gap may be identified.

SPINAL INJURY DIAGNOSIS AND PAIN MANAGEMENT

Spinal cord injury is assumed in unconscious patients and when symptom’s of back pain, difficulty breathing, weakness, numbness or paralysis in any limb is reported. This information will enable you locate the general area or level of spinal trauma and identify further injuries that may produce hypoxia (inadequate blood oxygen level) or hypovolaemic shock (dangerously low blood level and poor circulation) which compromise nutrition of a damaged spinal cord.

Control of the patient’s pain is important especially when multiple traumas have occurred. Initially analgesics are best provided intravenously. Administer slowly until comfort is achieved. Opiates should be used with caution when cervical or upper thoracic spinal cord injuries have been sustained and respiratory function impaired. Careful monitoring of consciousness, respiratory rate and depth, and oxygen saturation can give warning of respiratory depression. Securing the patient, environment, and collecting information in this way you can give medics a concise report upon their arrival and dramatically improve the short and long term outcomes for a person living with spinal cord injury.

Graham Streets

MSC Founder

RESOURCES

- David Grundy, Honorary Consultant in Spinal Injuries, The Duke of Cornwall Spinal Treatment Centre, Salisbury District Hospital, UK. Andrew Swain, Clinical Director Emergency Department, MidCentral Health, Palmerston Hospital North, New Zealand: ABC of Spinal Cord Injury: BMJ Books, 2002.

- Greaves I Porter KM. Prehospital medicine. London: Arnold, 1999.

- Toscano J. Prevention of neurological deterioration before admission to a spinal cord injury unit. Paraplegia, 1988.

- Andrew Swain. Trauma to the spine and spinal cord. In: Skinner D, Swain A, Peyton R, Robertson C, eds. Cambridge textbook of accident and emergency medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Go BK, DeVivo MJ, Richards JS. The epidemiology of spinal cord injury. In: Stover SL, DeLisa JA, Whiteneck GG, eds. Spinal cord injury. Clinical outcomes from the model systems. Gaithersburg: Aspen Publishers, 1995.

That girl looks so young. Whats here name. That’s gust sad